On Being Jewish

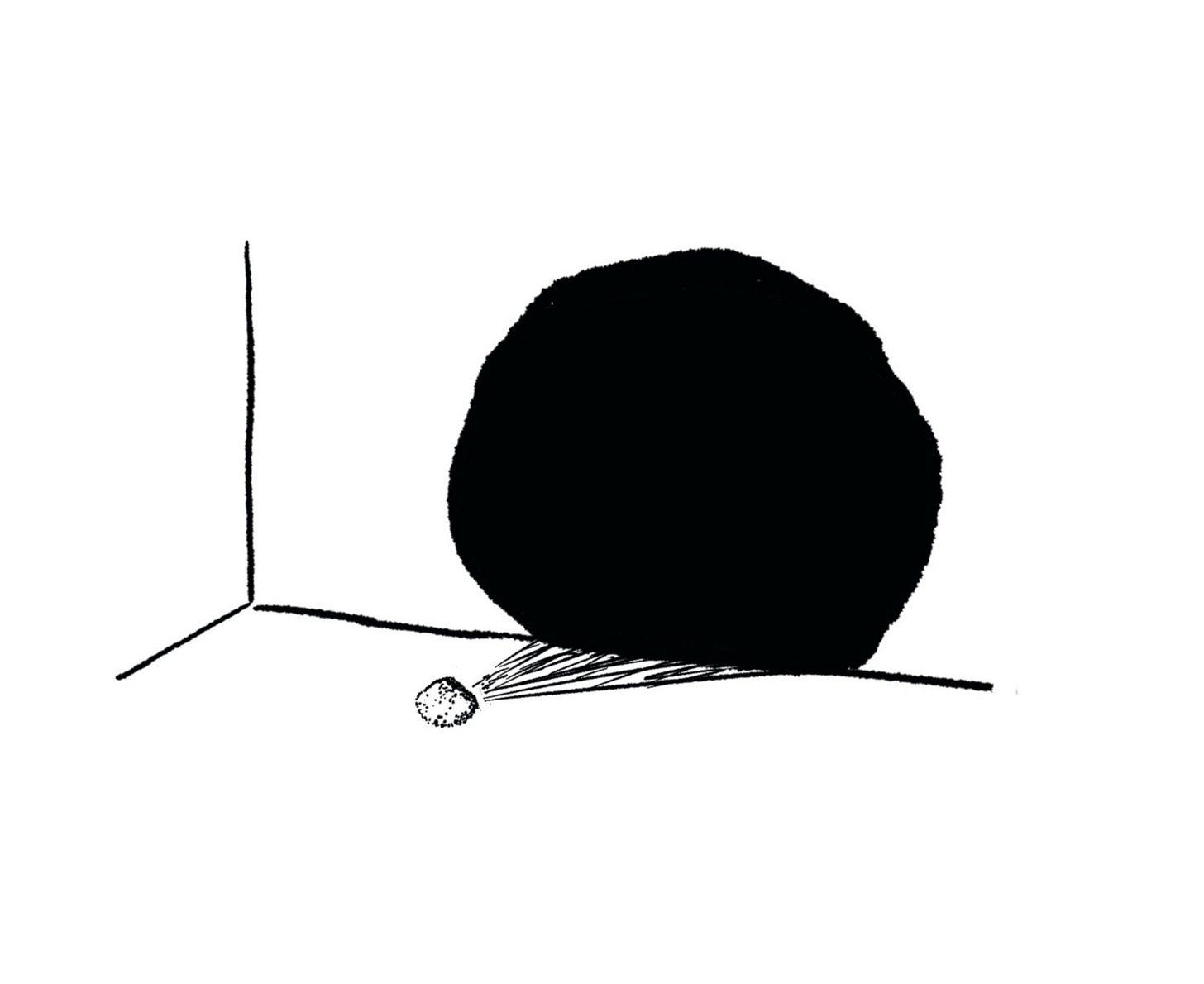

There is something inside of me I can’t get rid of. It weighs me down at the center of my body like a stone.

I am an American Jew, born in New York City and reared in the saintly suburbs of New Jersey. A diminished version of our family moved to Manhattan when I was about eight. Practically speaking, we were fatherless and faithless, but we had been that way for as long as I could remember.

In the 80s, being Jewish was a welcomed punchline, most often landed by Jews themselves. Chunk from The Goonies comes to mind—the pudgy little boy who made conspicuous reference to his Jewishness. Not to mention the comedic genius of Mel Brooks’s Spaceballs, which churned Star Wars lore and Jewish neuroses into alchemical gold. This was still, more or less, the golden age of Jewish comedians, a continuation of the indelible Borscht Belt comedy scene: Billy Crystal, Joan Rivers, Rodney Dangerfield.

Being Jewish was so normal, it was nearly forgotten.

Free Associations - TAP stories on cultural identity

A psychoanalytic candidate on the meaning of adopting a Western name

“Chosen trauma” and how to address polarization in groups

My Jewishness is a conflict. My mother was born a Catholic, claimed conversion, then later denied it. My father was born a Jew, remained a Jew in name only, then died of dyspepsia. To many Jews, I am not a Jew at all. To the State of Israel, I’m plenty Jew to apply for citizenship. To the denominations that trend conservative beyond Reform, I will never be a Jew. I have spent a significant amount of time worrying whether I’m Jewish enough, but I’ve spent an equal amount of time answering questions, as a Jew, about the West Bank, Netanyahu, and of course Gaza, as if my Jewishness, while perpetually in doubt, would always be enough by which to hang me.

I think about being Jewish a lot, more than most other Jews I know. I think about the disintegration of Jewishness, of which I am a part. I think about that most notably when people make anti-Semitic comments around me, not realizing (or fully realizing) that I am (or am not) Jewish. Sometimes I’m offended. Sometimes I feign laughter. I am a Jew. I am not a Jew. Ehyeh asher Ehyeh. I am what I am.

I’ve explored this inner conflict on the couches and chairs of several different psychologist’s offices throughout my life, gnawing my cuticles while my anxiety gnawed away at me. Of course, modern psychotherapy springs from similar Jewish neuroses—specifically the neuroses of Sigmund Freud’s Viennese patients, a great number of whom would not survive the Second World War. But many who did survive transmuted Freud’s genius through the postwar diaspora, making New York City—my home—a hotbed of psychoanalytic thought and practice, while others made Palestine a home to the Jewish State.

I am an American Jew. At this point, it’s more of a choice than a conscription.

When the brutal attacks of October 7 happened, I was scared, but not of a further incursion by Hamas into Israel or the wider war into which Netanyahu’s cabal of the extreme and the inept would inevitably—and enthusiastically—be drawn. I was scared about being seen. Being unforgotten. Early Jewish opponents of Zionism, namely the Jewish European socialist labor movement Bund, argued that the most dangerous thing for Jews would be an ethnoreligious state, that, paradoxically, a Jewish state would stoke the flame of global anti-Semitism, which at the time had been kept at a comfortable simmer. “Comfortable simmer” being a consistent program of Jewish annihilation, tacitly—and often overtly—backed by world governments. My family fled one of these pogroms in Ukraine during the latter part of the 19th century, escaping the Pale of Settlement for the shores of New York with nothing but what they could carry. In America, my father’s family found a path to survival by way of alacritous integration and assimilation. They were Jews always. But now they were American Jews, and for the purposes of brevity and peace, just simply Americans.

When I think about Israel, I think about New York. New York is my Israel, as it is to the second largest concentration of Jews in the world. I think about the Haredi boys, the Lubavitcher knuckleheads who try to wrap tefillin around your arm as you exit the Bedford stop on the L-train in Brooklyn. I think about my schoolmates, my friends who argued over bagels and baseball teams. I think about the community, both acknowledged and hidden, in our conversations and in the culture at large. “You know,” my father would often whisper, pointing out some minor character on the screen at the movie theater, “he’s Jewish.”

On October 7, I was scared. When the tanks rolled into Gaza, I cried. I cried because I knew, right in that moment, as did every other Jew in the world, that everything that has happened since would happen. Children would be murdered, families incinerated, communities destroyed, all while world governments bent themselves into more and more complex contortions and contradictions to excuse—and fund—the inexcusable. Some of my friends would become extremists, refusing to either acknowledge the vicious brutality of the October 7 attacks or the horrors playing out daily in Gaza, as if both of those realities could not possibly exist in the same universe, trading the nuance of our tortuous existence for the tiny death of Twitter’s 280-character limit.

I am an American Jew. At this point, it’s more of a choice than a conscription. I’m lucky that way. I could easily toss off my Jewishness and present my auburn hair as a product of Celtic descent, my brown eyes and pallid features as vaguely European. They may well be. But there is something inside of me I can’t get rid of. It is not belief. It is not faith. Yet it weighs me down at the center of my body like a little stone, an artifact buried in my gut, reminding me of the generations of unimaginable pain and loss that was given in exchange for my existence, an existence that would forever question its own validity.

All this plays out in a nanosecond before I answer any question about Gaza. On the one hand, I see what is to me a purposeful and targeted genocide by a murderous and corrupt Netanyahu regime; that any ethnoreligious state is in direct conflict with democratic ideals, no matter how many people take to the streets of Tel Aviv; that conquerors and colonists will never have rightful claim over a land and its people, even if some of those conquerors and colonists have been there for centuries; and that there is no such thing as divine right.

This all seems clear and unequivocal to me.

But there is also, simultaneously, the fear of even asking for preservation. It is a familiar fear, burnished and kept hidden in the body of every Jew.

Alex Dezen is a writer, songwriter, and graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. He fronts The Damnwells, a cult-favorite indie rock band, and coedits Nulla, a journal of literature and art. His fiction has appeared in The Masters Review and more.

Submit a question to advice@tapmag.org.

Thank you for sharing such a raw and powerful expression. Your words carry deep emotional and moral weight, and they come from a place of profound conviction. They reflect the anguish of witnessing enormous suffering in Gaza, and the frustration at what feels like global inaction or complicity. These are not light matters—and they deserve serious reflection, not defensiveness or deflection.

As a Jew, I want to speak to you not in opposition, but in deep conversation—because these moments ask us not only for clarity but for compassion. And compassion must stretch in more than one direction.

I carry the grief too. I grieve for the families in Gaza. I grieve for the destruction. But I also carry a different kind of weight: the burden of being Jewish in a time when once again, Jewish identity is equated with the worst imaginable crimes. I carry the echoes of history—the blood libels, the propaganda posters, the accusations that Jews, by nature or faith, are responsible for harm, manipulation, control. Today, those old tropes are dressed in new language: ethnic cleansing, apartheid, genocide. And while there must always be room to critique Israeli policy—harshly and truthfully—the collapsing of Israel into a singular evil often leaves no space for Jewish fear, Jewish complexity, or Jewish trauma.

You speak of genocide. That word should never be used lightly. It invokes the darkest acts humanity can commit. But many, including international legal scholars, argue that the situation in Gaza, however horrific, does not meet the legal standard of genocide—which requires a clear intent to destroy a people as such. The Israeli government says its target is Hamas, an armed group that launched an attack on October 7 that left 1,200 people dead, hundreds raped, burned, kidnapped. The war that followed has been brutal. Many of us wish it had not happened. Many of us believe the current government is corrupt and destructive. But believing it is genocide—that Israel is trying to exterminate the Palestinian people—requires ignoring a mountain of counter-evidence: the warnings to civilians, the attempts (however flawed) to allow aid in, the internal dissent within Israel itself, and the many Jews who oppose the war and defend Israel’s right to exist.

You reject the idea of a Jewish ethnoreligious state. I understand why. It feels exclusionary, unjust. But I ask you to consider this: Israel was born not only from the ashes of the Holocaust, but also from the flames of expulsion, humiliation, and violence faced by Jews across the Middle East and North Africa. Over 850,000 Jews were driven out of Arab and Muslim lands in the 20th century—many with nothing but the clothes they wore. Today, roughly 70% of Jews in Israel descend from these communities. They cannot “go back.” There is no return. Their synagogues were torched, their cemeteries destroyed, their histories erased. For them, and for us all, Israel is not a colonial project—it is home. It is refuge.

And that refuge must be defended—not out of blind nationalism, but because there is no other. It is the only Jewish-majority country in the world. And while the world tells us that Israel is a failed state of oppression, the truth on the ground tells a more complex story. Within Israel’s borders, Arab Muslims, Christians, Druze, and even ancient groups like the Samaritans not only live—they grow. Their populations increase steadily, their children attend universities, serve in Knesset, become doctors, lawyers, artists. In fact, the Christian population in Israel is the only one in the region that is growing. In neighboring countries—Syria, Iraq, Egypt, Lebanon—minorities are vanishing under persecution or war. Where are the mass protests for them?

So while we must always interrogate Israel’s actions and policies, let’s also remember: Israel is not the worst of the Middle East—it is, in many ways, the exception. And rather than burying our heads in guilt that is not ours to carry, we can feel something else—a complicated but earned pride. Pride that in a region where minorities are hunted, we have built a country, flawed but resilient, where minorities grow. Pride that we have welcomed waves of refugees, from Ethiopia to Russia to Iraq to Yemen, and made a fractured people into a society. And pride that we still argue, still protest, still demand more from ourselves—that is not apartheid, that is democracy in anguish.

You call Zionism colonialism. But Jews did not come to Palestine as colonists of empire. They came as refugees, as dreamers, as survivors. Many bought land legally. Many lived alongside Arabs in peace. And yes, there was displacement and war—wars fought in 1948, 1967, and again and again—wars in which Jewish survival was not guaranteed. That doesn't erase Palestinian suffering. It doesn’t justify injustice. But it complicates the story—and to call all Jews in Israel colonists, conquerors, or foreign invaders is to erase the deep historical and spiritual connection Jews have had to that land for thousands of years.

And finally, you reject divine right. I do too, in many ways. I don’t believe land belongs to anyone because God said so. But I also know that for many people—Muslims, Christians, Jews—faith isn’t just a private belief. It’s a part of their history, identity, and longing. And for Jews, the idea of returning to Zion wasn’t a slogan. It was a 2,000-year prayer.

None of this is to deny the suffering in Gaza. It is horrifying. It should shake us. It should demand response, and restraint, and accountability. But I ask—gently—that in your moral outrage, you don’t lose sight of the complexity, the trauma, the context. And that when the world chants in accusation, you leave some space for Jewish pain too.

Because we all want a future without war, without displacement, without walls. But we won’t get there if we deny each other’s stories.